By Keith Wood

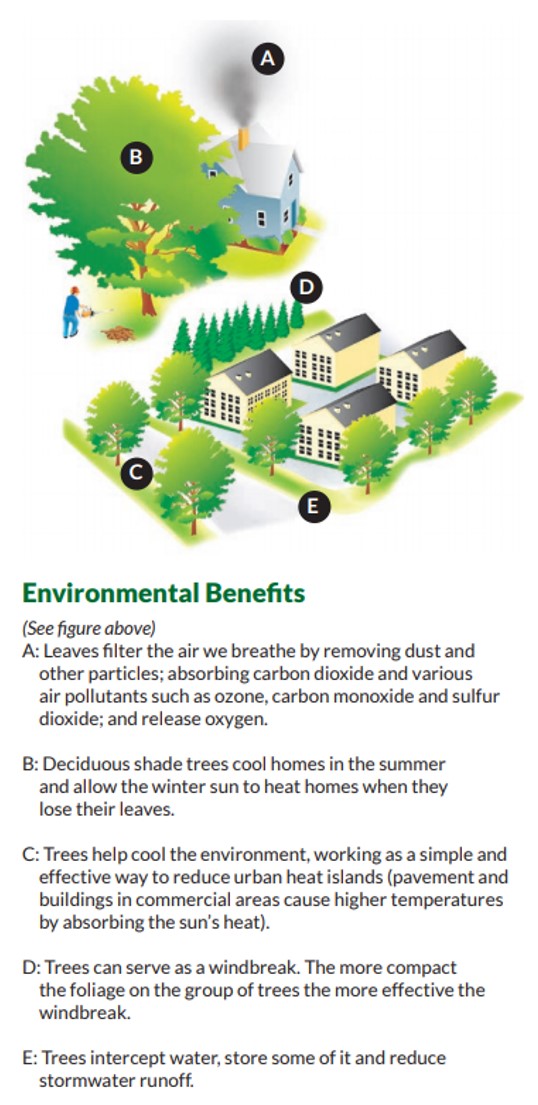

If you live in a city or town, did you realize you actually live in a forest? It is estimated that 138 million acres of trees comprise the urban forests in cities and towns across the United States. These forests span many ownership boundaries and provide numerous environmental, economic, and social benefits to communities and their residents.

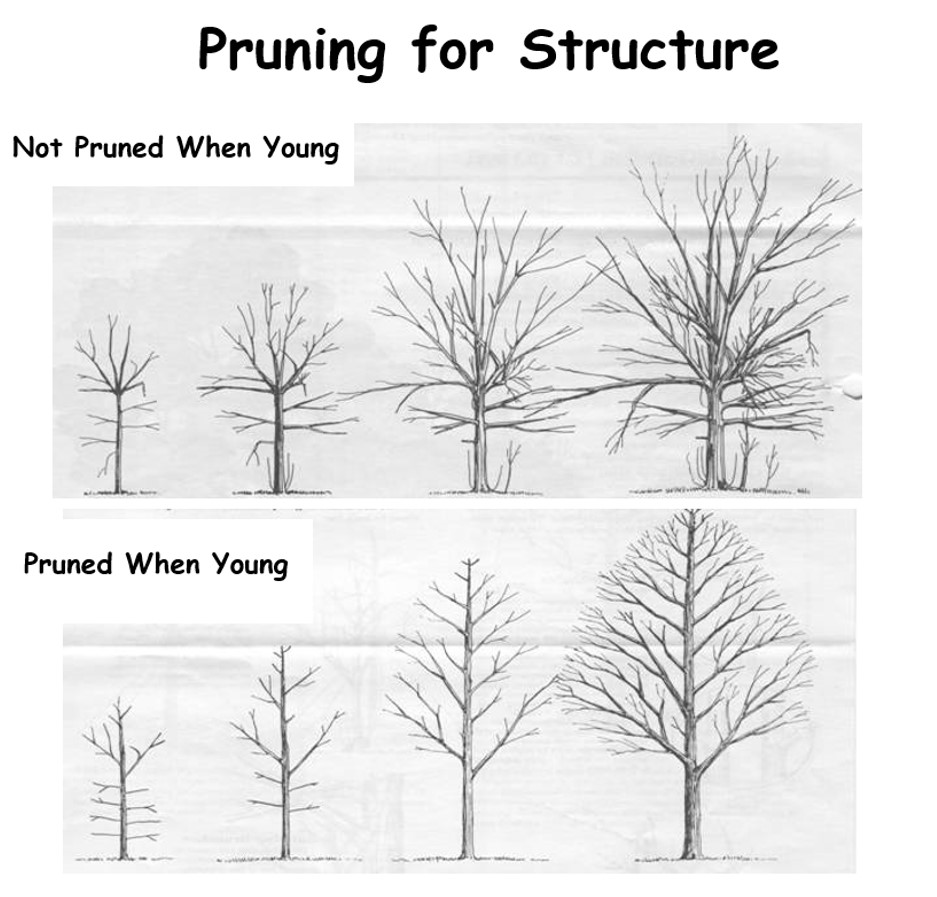

Urban and community trees also come at a cost. Growing, selecting, planting, maintaining, and eventually removing trees all can be expensive. Compare the trees below: which one will live a long, benefit-providing life in the landscape and which one will soon become a liability? Working on a tree’s health and structure when young greatly pays off in benefits from that tree as it ages.

A primary goal of urban forestry management programs is to maximize the benefits trees provide over time, while minimizing maintenance costs. Ultimately, towns and cities want to realize a net positive rate of return on tree planting and care investments.

While many communities are able to budget and care for trees on public properties, often times the trees on private property, which can constitute up to 80% of a community’s urban forest, are left behind. Many trees on private property across America are succumbing to age, climate change, insects and disease, and other environmental stressors, causing tree management challenges for many communities.

Recent success stories from California, Oregon, Wisconsin, and Maine show just how state forestry agency programs are helping private landowners minimize costs and maximize benefits of trees and urban forests.

In the Pacific Northwest, the Oregon Department of Forestry is promoting tree planting and the community-building capacity of tree planting programs by distributing Hiroshima Peace Trees to communities all over the state.

In California, CAL FIRE is using an environmental justice tool (EJ Screen) to identify communities that need assistance with urban tree planting to increase canopy percentages and minimize heat, air quality, and stormwater issues.

In the Midwest, a Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources program is working directly with the Urban Wood Network to ensure trees removed from urban forests are utilized in forest products and continue to sequester carbon for years to come.

In the Northeast, the Maine Forest Service is working to minimize the damages caused by emerald ash borer in urban tree canopies and replace removed ash trees with diverse tree species.

These state programs are just a select few enhancing urban forests — every state has an urban and community forestry program. As more tools become available, such as EPA’s EJ Screen, Redlining Maps, Heat Island Index Maps, Income Disparity Maps, etc., state forestry programs will be developed to help focus resources in areas with the greatest need for tree planting, tree care, and tree removals. “Right tree, right place, for the right reason” can (and should) play a significant role in these programs. Similarly, urban forestry management plans can (and should) include goals that benefit the large percentage of trees that occur on private property.

Property values are likely to increase as hazardous trees on private properties are removed and risk is reduced. Tree care and landscaping companies could see an increase in jobs as a result, and state forestry agencies may be able to support new positions in eligible communities with grants. Local resources, codes, regulations, and best management practices can ensure communities are successful in the long term.

Urban forests are one of many ways state forestry agencies and local communities can contribute to the Biden administration’s climate change, environmental justice, and workforce development priorities. NASF looks forward to working with the White House, federal agencies, and Congress to realize the tremendous potential of urban forestry. This briefer gives an overview of the power of urban and community forestry.

Want to learn more about urban and community forests? Get involved with the NASF Urban and Community Forestry Committee by reaching out to staff member Keith Wood.